Step Two: staging of Twin–Twin Transfusion Syndrome

Our current understanding of the heterogenous presentation of TTTS explains the seemingly conflicting reports of pioneer investigators regarding the role of Doppler in TTTS.9–13 Indeed, we now know that only a subgroup of TTTS patients present with abnormal Doppler findings.

Thus, Doppler studies are more important in terms of assessing disease severity rather than in defining the syndrome. TTTS is known to be a heterogeneous condition with different presentations. Variations of the syndrome include visualization or lack thereof of the bladder of the donor twin, and the presence or absence of abnormal Doppler studies or hydrops.

TTTS may also present with demise of one or both twins. The heterogeneity may result as a direct consequence of determinant factors (e.g. abnormal Doppler studies due to placental insufficiency, or severe hemodynamic decompensation or superficial anastomoses), or more often, the expression of dynamic changes occurring over time, which eventually may result in demise of one or both twins. In 1999,8 we proposed a sonographic staging system to account for all of the different presentations.

Inherent in the staging system is the notion that the higher the stage, the worse the prognosis. For all stages, patients meet the basic criteria of polyhydramnios (MVP ?8 cm), and oligohydramnios (MVP ?2 cm). The staging system is as follows.

Stage I

The bladder of the donor is visible (Figure 7.6).

Stage II

The bladder of the donor is not visible (Figure 7.7). The typical ultrasound examination of patients with TTTS lasts approximately 60 minutes.

Non-visualization of the bladder of the donor therefore is defined as lack of visualization of the bladder of the donor twin in 60 minutes of ultrasound examination.

Stage III

Critically abnormal Doppler studies.

These include:

• absent or reverse end-diastolic velocity in the umbilical artery (UA-AREDV) (Figure 7.8a–c).

• Reverse flow in the atrial contraction waveform of the ductus venosus (RFDV) (Figure 7.9).

• Pulsatile umbilical venous flow (PUVF) (Figure 7.10a,b).

There is no controversy regarding the definition of UA-AREDV. However, it is important to note that AREDV may be artificially created by setting the wall-motion filter (WFM) too high. The standard setting of the WMF is 100 mHz. Occasionally, patients may show intermittent UA-AREDV. In these cases, the patient is staged as having positive diastolic flow. Similarly, if UA-AREDV is noted closer to the fetus, but diastolic flow is detected closer to the placental insertion of the umbilical cord, diastolic flow is considered to be present.

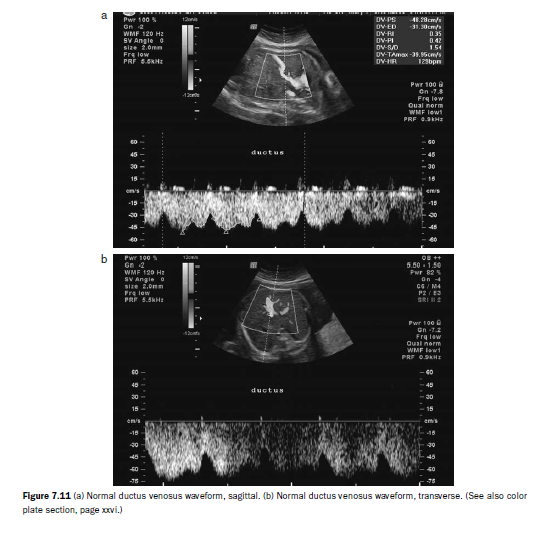

Doppler interrogation of the ductus venosus can be particularly challenging in the assessment of patients with TTTS. Care must be taken not to confuse the waveform of the ductus venosus with that of the hepatic veins or the inferior vena cava (Figure 7.11a–e: DV, hepatic vein, IVC).

Similarly, the WMF should be set at 100 MHz. For the purposes of the staging system, flow in the ductus venosus must be reversed during the atrial contraction waveform to be called critically abnormal, and not merely absent (see Figure 7.10).

Similarly, the WMF should be set at 100 MHz. For the purposes of the staging system, flow in the ductus venosus must be reversed during the atrial contraction waveform to be called critically abnormal, and not merely absent (see Figure 7.10).

Pulsatile umbilical venous flow is considered to be present whenever Doppler interrogation of the umbilical vein shows a non-linear pattern (Figure 7.10a). The waveform is obtained at the level of the umbilical cord, not in the intraabdominal portion of the umbilical vein. It is important to note that PUVF represents a different pathophysiological phenomenon from RFDV, as the latter occurs during diastole, whereas the former flow is typically a systolic abnormality. As such, RFDV and PUVF may coexist or occur independently in any given fetus.

No comments:

Post a Comment